However, the central question posed by the book is whether there is value in photographs of suffering and how or even if we should look at them. She discusses the photography of a number of major horrors the world has suffered, the Nazi Holocaust, The Chinese Cultural Revolution, Post War Central African Conflict, and the combination of Abu Graib and Terrorism. In each case she analyzes the politics, the cultural impact and the way in which photography has served both as witness but also as a means for survivors to deal with the terror they endure. She has a clear political stance but reading this book I did not feel dictated to, rather that I could make up my own mind on these subjects.

A key difficulty in the photography of violence it that the pictures are frequently created and collected by those responsible for the violence, victims rarely have the chance to document their own pain. These images, such as those taken by Nazi soldiers in the Warsaw Ghetto pose the most difficult question in how we should look. These are images taken of humiliation, the subjects humanity is further eroded by the act of photography and yet these images are sometimes the only remaining document of these peoples existance and are damning evidence of the cruelty inflicted. My conclusion is that we should look at these pictures, but again with context and an understanding of how and why they were made. I find it important to know that the photographer was complicit in the abuse and not merely a witness.

She finishes by looking at the career of three famous conflict photographers, contrasting their styles and trying to understand their motivation. The photographers are Robert Capa, James Nachtwey, and Gilless Peress, 3 very different, but influential artists. In analyzing each photographers work the most interesting discussion is around style and presentation, Capa seems very natural not attempting any sophisticated framing, simply reportage, whilst Nachtwey is seen as making the obscene attractive, applying art to pain. Perhaps this is why he refused to allow his photographs to be reproduced in this book. The authors opinion seems to be that capturing and revealing pain and suffering at the hands of others is a socially important act, however, portaying it as art is not.

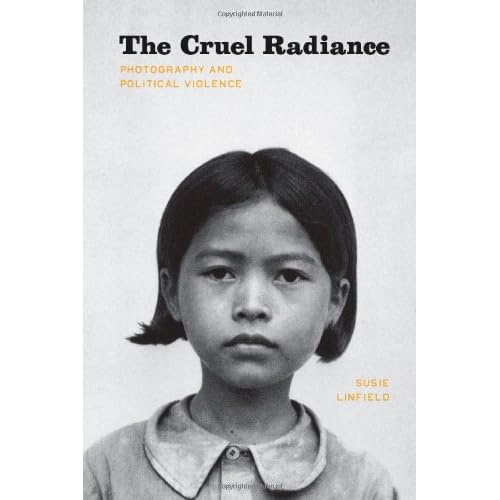

I think this comes back to the long lasting debate about photography frequently being the study of those without by those with. My final comment about the book is that it is very light on illustration, there are 1 or 2 images per chapter, but no more. In the text she repeatedly refers to images that are not in the book. Perhaps this is a good thing, these are not easy photographs to look at for all of their importance as document. The picture on the cover is of a 7 year old girl photographed shortly before her "execution" by the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia, her crime simply being. One can only look at so many photographs like this.

No comments:

Post a Comment